Software Demystified: How does a Text Box Work?

Below is an excerpt from Street Coder , where Sedat Kapanoglu talks about opacity in software.

“Technology is becoming more opaque, like cars. People used to be able to repair their own cars. Now as the engines become increasingly advanced, all we see under the hood is a metal cover, like the one on a pharaoh’s tomb that will release cursed spirits onto whoever opens it. Software development technologies are no different. Although almost everything is now open source, I think new technologies are more obscure than reverse-engineered code from a binary from the 1990s because of the immensely increased complexity of software. ”

I agree with these sentiments, and actively argue against this opaqueness. This article is part of a series of Software Demystified articles that will try to build up components or systems we use in our everyday software development such as text boxes, search bars, or databases in the hope of removing some of the opaqueness in our understanding of these systems.

So, what is a text box?

This is actually a pretty good and important question, especially because it doesn’t have a right answer. A Text Box can be growing or fixed height, it might overflow vertically or horizontally, it might be multiline or single line, it can support emojis, or allow rich text editing, may be WYGIWYS or more verbose, it can allow for directives such as mentions, or spoiler marks.

Aside from these features, the maximum allowed text size or trimming characteristics, keyboard shortcuts, rendering, mouse interactions are all part of the requirements for implementing a text box.

In an ideal world, we would have a model of the text box that defines how any action transforms the state of the text box as below.

This model of course depends on the internal data representation of the text box.

Let’s start with the one of the simplest text boxes possible.

Textbox V1

1. No mouse actions.

2. No ctrl/alt/shift actions.

3. No newlines.

4. Fixed width and height, grows to right.

5. No rich text, fixed width font.

This text box, in essense, has only 3 features.

- Add/delete a character

- Have a cursor and move the cursor using left/right arrows

- Focus the text view with respect to the cursor

So, what are the tasks for the developer here?

Well, the programmer has several jobs. The first one is the rendering. Given a set of characters, we need to render those to the screen. We don’t need to implement the rendering itself, but we need to know certain properties of the result in order to correctly determine the position of the cursor as well as what portion of the text to render and where.

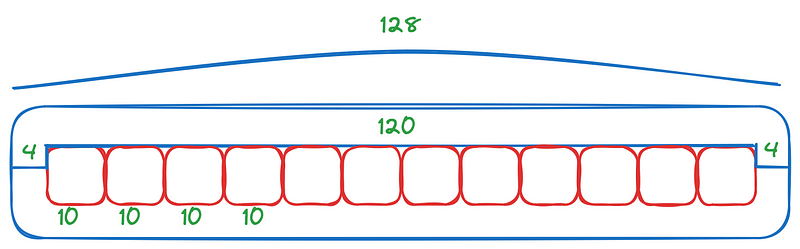

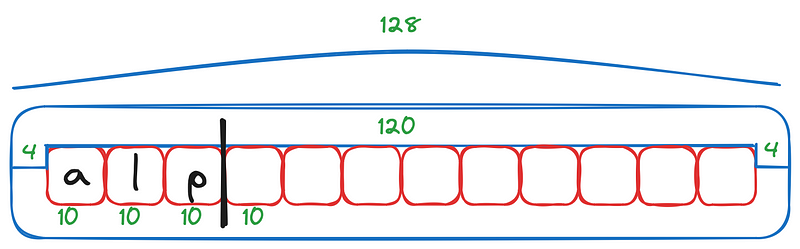

Simplification number 5 plays a big role here, because we have a fixed width font, meaning that each character has the same width, (1) we immediately know the amount of characters that fit in our box, (2) we can find the position of our cursor very cheaply. If our box is 128 pixels and we have a fixed character size of 10 pixels, we can leave 4 pixels of padding in each side and have exactly 12 characters in the text box.

As we start typing in characters, our cursor moves automatically with each hit to the keyboard.

Our cursor has

length(text) + 1

potential positions, before the first character, between the characters, and after the last character. One funny thing that I just realized is we could also specify the amount of consecutive spaces. Medium’s text box interestingly only allows for one consecutive space character, I wonder why.

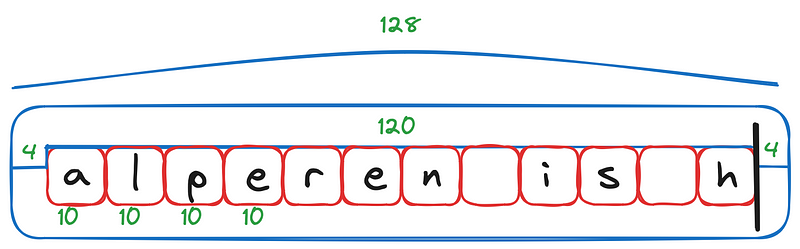

Hitting 12 characters is the first point our action has a different result. Before now, we rendered our text by starting from the very first character by leaving 4 empty pixels, then rendering each character with 10 pixel distances, deciding the position of the cursor by calculating

4 + cursor_position * 10

. Each typed character has increased the

cursor_position

by 1, and each deletion decreased it by 1, capped at 0. Now, we reached the case where

cursor_position == 12

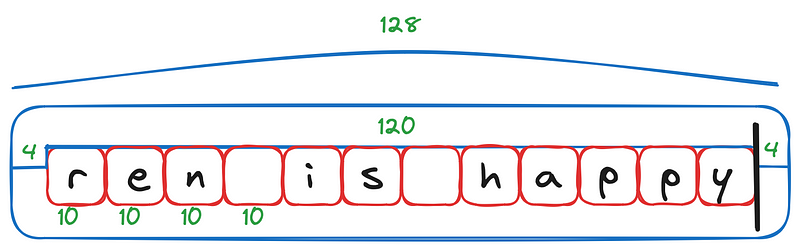

, in which any new character does not change the cursor position, but rather changes the window of the text we render. This is easily doable by adding a

starting_position

that tracks where the rendering window of the text begins.

Now, we need to specify the

starting_position

characteristics. Luckily, they are very easy, most of the time starting position does not change. It only changes when

cursor_position == 12

and the action tries to increase the cursor, or when

cursor_position == 0

and the action tries to decrease the cursor. (there is one extra case that I forgot to write in my first trial, I encourage the reader to think about what that is, as you see, it’s quite tricky to correctly specify the behavior of even the simplest version of the text box)

Above, you can see how the window slides as we add new characters.

This is probably all we need to talk about TextBox V1. What are the next steps though?

An easy thing to do is remove the first limitation and allow for mouse clicks. As we can easily determine the character at which mouse click happens, we can move the cursor at the end of that character. A harder mouse action is drag action, in the user presses the mouse at some character and drags the mouse to another part of the text. This behavior has the same computational model as shift + arrow keys, so implementing one gives us the other for free. The behavior is very similar to the cursor movement + text sliding described above, but it also requires us to remember where we started.

Adding ctrl keys requires finding the first whitespace and jumping at the point.

Adding new lines adds a new dimension to the box, where our actions can also have vertical movements. It also opens up the possibility of changing the data representation to use paragraphs or lines instead of a simple text, because for long texts, it would be vastly inefficient to implement them in terms of simple strings.

Adding variable-width font complicates our cursor position calculations, line break computations, as well as mouse behaviors, because now it is much harder to determine how the original text is presented in the text box in a visual way. Before, the complexity was virtually constant, now it might be linear with respect to the size of the text.

Adding rich text(colors, font sizes, font styles) requires us to create separate text runs that represent parts of the text with different qualities, and render them consecutively. Rich text also complicates the position calculations even further, because it prevents approximations. With a single style variable font, we can have a constant time approximate result, which is linear with respect to the number of text runs in a rich text setting.

Why are all of these important?

To be fair, they probably aren’t if you are not developing the next blogging site, a new text editor or a new messaging app, hell they probably aren’t important even if you are doing one of those things because you would be using already existing components. The information in this article is more interesting than it is useful, and I think it allows for a rare type of thinking where we look behind the curtains of the opaque software world. I like to look behind the curtains, because I don’t like it when I am limited with the options available to me today, using the standart implementations available. I like to be limited with my own creativity.